NATALIO ARTIGAS PUJOL, ITINERARY OF AN UNKNOWN MAN

Recoleta Cultural Centre | Buenos Aires | 1994

TRADITION

The word ‘tradition’ (in Latin, traditio: “the act of transmitting”) comes from the verb tradere; to hand over, to give, to deliver. Its meaning in general is related to “transmission”. But the word ‘tradition’ is not reduced to simple conservation and transmission of what has been previously acquired. Over the course of history, tradition “makes what has been be again”.

The act of transmitting and the act of inventing constitute two specifically human operations. When a community preserves and transmits its knowledge, it ‘recreates’ itslef by making what it has been, and what it wants to be, “be again”.

INTRODUCTION

I have always been enlivened by the stories of men of adventure; going through those individuals’ unspeakable emprises drew me closer to my own dreams and desires.

History is full of men like these, whose naivety and craving fill the most amazing pages of our brief transit in this world, each one leaving its small or great mark.

But there are also the others, the ones whose passing left a trail so slight, following their steps is like tracing the forgotten pathways that time has erased.

Trails that attempted to become paths, signals, and now witness the unsettling search for unfound certainties.

In the search of our own dreams, we discover these trails that awaken in us, once again, the exciting taste of adventure.

But what constitutes the adventure that lies behind our desire to sail on to uncharted waters? It is difficult to even imagine a corner of our world that hasn't been stomped by civilized feet, or in which the unique transparency of an almost virgin secret still hasn't been broken.

Nevertheless, we sail on to unexplored territories, searching not for geography but for sensations... looking for the endpoint that reveals to us the magic in this life.

These documents are a part of those dreams.

They take us where the extraordinary is still possible. They show us stories that were once dreams, and dreams that became history.

The only purpose of gathering, organizing and publishing these documents is to awaken those dreams once again.

They testify for man's unstoppable struggle to build his present and to give it a meaning that takes him to higher goals, where everything starts to gain meaning solely by attempting so.

Throughout the centuries, traditions of all kinds gather the stories of the ones who came before us, which are now a part of the most varied legends and tales. Many of them contain true stories; many other roam in the unsettling stream of imagination.

But in all of them there is the desire to build something new, to edify a tradition that recomposes us and tells us where we come from and where we are going to.

MYTH AND REALITY

When the first photos of Natalio landed in my hands, I couldn’t stop imagining the reach that the attempt to draw a clearer image of him might have. His history took shape along with that of our grandfathers, even though Natalio held the craving of the settler, of the expeditionary, of the adventurer who rummaged in the confines of this earth. But the difference lies in that he entered the fields of fiction and science. His means never ceased to be imaginative.

During one of my stays in Montevideo, while gathering information about his work and his story, I unexpectedly found more than what I had imagined.

His work, compiled during the last years of his life, was found carefully displayed in several boxes, bound and indexed, handwritten.

The tenants of the old house that was once his home had preserved the documents, awaiting an institution to take upon them.

Once again, destiny had intervened to avoid their inevitable loss and, judging by old photographs of his studio, the reconstructions he made had been lost forever. But his manuscripts, documents, drawings and maps constitute some of the richest pages of our history.

The following chapter would start taking shape in the South Argentinian Railways General Archive, where it’s possible to trace his steps through one of the darkest periods of his life.

Scarcely some fragments that would connect him definitively with his stay in Patagonia, and would help shaping one of his most discussed theories. His story could be one of many.

Our past blurs and reconstructs itself through our memory. And so, our past ends up being what we make of it.

Our wish to reconstruct it is but another way to reweave the weft that constitutes us. The threads that compose it lose their color with the pace of time, but they define what we are and tell us about what we try to be.

These are Natalio Artigas Pujol’s found documents. His existence, however, is already part of a myth.

Leonel Luna

Natalio Artigas Pujol, 1894-1959

Son of a wealthy oriental landlord of Catalan origin and a Venetian mother, he settled down by this side of the river by the middle of 1908, in the company of an aunt and his little brother, who would die a year later of yellow fever.

His father would finance his studies in Europe, allowing Natalio to locate in Paris (1912) where he would visit the British Museum halls. During one of his many strolls through London, he was deeply impressed by Egyptian archeological remains. From then on, he would begin an important career that, although it would be unfairly ignored, does not cease to amaze us for the audacity with which he explored the field of ideas that shocked some blind peers of Victorian spirit.

But it was in Paris where he became acquainted with and studied the works which August Le Plongeon had carried through on Mexican land (1826 – 1908), and it didn’t take long for him to subscribe to the theories exposed by Englishman Churchward (1850 – 1936), who at the time was publishing his second book “The Sons of Mu” (1931). In his first work “The Lost Continent of Mu” (1930), he accounted for the great underwater continent of Mu, located between America and Asia and with its centre positioned slightly in the south of the equator.Churchward’s theories, which went from the archeological field through anthroposophy, with elements of masonry, left in young Pujol the latent impulse which he would develop in South America some years later.

During his stay in Montevideo, he reconnects with his old friend Juan Ramírez Torres, native of Tandil and with whom he maintained plentiful correspondence, who invites him to his country house in the highlands. Pujol agrees and so begins his trip through the Buenos Aires highlands, east Patagonian region and lakes of the Chubut mountain range, searching for details on the ancient myth of the “city of the Caesars”.

Pujol arrives to what he believes to be the traces of an age-old civilization, bastard offspring of Mu’s third migration.

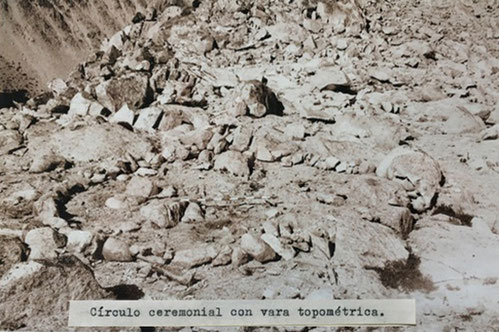

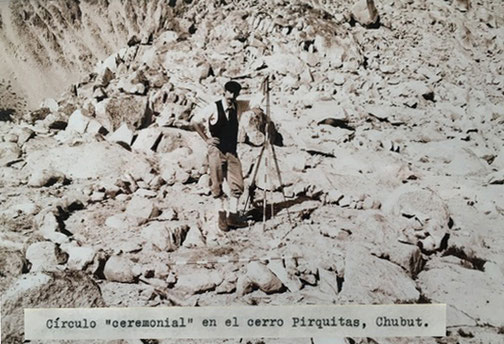

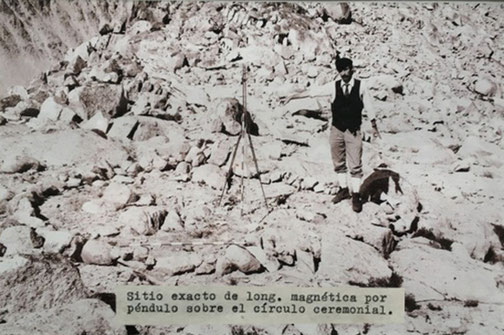

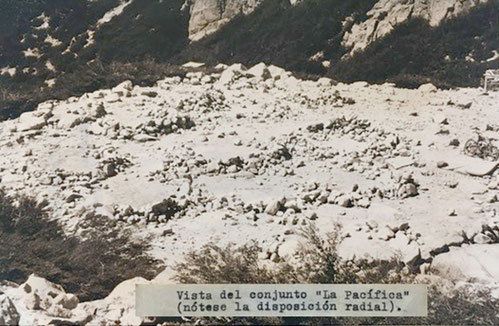

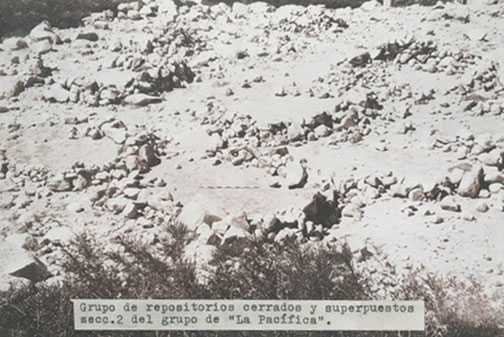

He conducts his first excavations and surveys finding primitive, stone-made constructions, unbound, and of diverse continuous circular shapes.

He also finds coarse ceramic remains, although too damaged for reconstruction, which suggest zoomorphic configurations that randomly repeat shapes as those of rodents and camelids; venturing daring hypothesis.

He returns to Buenos Aires, where he unsuccessfully seeks funding for further excavations.

Many authors had before formulated hypothesis on the existence of highly developed civilizations existing ahead of the Incas, the Mayas or the Olmecas. But since there were neither a historical record of such ancient times nor a precise system to date the remains, these stories were left to float in a limbo between reality and fiction.

Nevertheless, “the accumulated evidence is of such significance that it cannot be ignored”, he wrote in his notebook towards 1929. Around the same time, he describes a surveyed area in Tandil of around 52 km2 (32 mi2), which marked a cosmogonic configuration that would demonstrate the use of astronomic concepts absolutely unknown to their Puelche probable contemporaries.

According to his data, the “Chechen-het”, known to white men towards the end of the last century, would be merely a fistful of those forefathers from whom they only recalled old and diverted legends depleted with the last massacres in the Ventania region (Province of Buenos Aires).

By the mid-1930s, Pujol is pushed by the economic crisis to work in the National Railway, thanks to his uncle (prominent engineer in the construction of the Patagonian branch line of the then South Railway, now known as Roca Railway), on the position of sub-intendant of railway provision. He seizes the opportunity to establish contact with the local natives of the region of the current Ing. Jacobacci station, from where he gathers testimonies that today are of great anthropological value, and that he would use in defense of his theories about the ancient Mu-descending civilization.

Economic hardship, and the sickness that was afflicting his by then elderly father, make him go back to oriental lands, where he writes and develops his investigation, which was never to be considered by the scientific world, partly for not fitting the established ideas, but also because his theories were exploited by sensationalist media which ended up discrediting his accomplishments.

Until, finally, the news arrived of the astonishing findings by Scotsman William Niven on Mexican lands, which proved Churchward’s statements about the continent that gave origin to some of the civilizations that later spread across the globe (it would be subsequently confirmed that these findings had been a fraud).

Counting on the capital inherited from his father, he settles in Buenos Aires, where the statements on his findings are appreciated. He decides to finance his own investigation while sending details on his work to the Ethnology Institute of the University of Paris, without ever receiving an answer.

Through a good friend of his father, who owned some lands in Tandil, he relocates to Santiago Gorostiarena’s estate, who invites him particularly.

A wealthy son of Buenos Aires province estate owners, Gorostiarena was keen on the coteries involving the most varied characters of that time. Educated in the best schools in Buenos Aires and devoted to arts and science, he enjoyed listening to the most fabulous stories.

Besides being a part of a French Masonic Order, he found in Pujol a conversation partner of his own calibre. Other “protégées”, who Gorostiarena sponsored in many projects, would also assist to his evening meetings.

Pujol found the moral and economic support he needed to continue his endeavour, backed by Gorostiarena and a friend of his, German Adam Sonnenschein, who designed a device that measured radiesthesic emissions which appeared to be very elevated in the area.

Sonneschein’s device had a shimmer counter, which detected mostly “hard” radiation of greater frequency -which has a high penetrating power- and, specially, neutron emissions. First, it detected undercurrent radiation and, when transporting it using its wheels through the studied area, it registered variations in the existing radiation. Sonnenschein called his device Cadactron. With this new technology, he was able to perform much more precise measurements than with the traditional “Zahori Dual Rods” – it allowed him to detect “highly magnetic areas” in previously excavated archeological sites, and to discover new “radiesthesic enclaves”, which he quickly started investigating.

In a letter that he wrote to his friend Armin Bickel he says: “I have no doubt that the previous works I had been elaborating are but a sample of something much greater that I’m beginning to sense”.

But by the end of 1938, Pujol, excited with his project, had squandered his lean fortune and Gorostiarena, harassed by family lawsuits, had long stopped financing his experiences.

Feeling distressed and misunderstood, he takes refuge in a Trappist monastery in the town of Azul.

Later on, back in the city of Buenos Aires, he sorely survives by giving conferences and publishing, on the “Atlántida” magazine, reports and articles under different pseudonyms in which he accounts for his theories and investigations.

He later relocates in an uncle’s house in the town of Buratovich (Province of Buenos Aires), south of Bahía Blanca, from where he plans to find the traces of the old roads used by Tehuelche hordes to herd stolen cattle onto Chile - a required route laid out from the Buenos Aires highlands and that was also used as refuge and shelter.

By mid-1945 he receives support from the Catalan Society of Bahía Blanca for what would be his last enterprise: assessing more than 45 new radiesthesic-archeological sites in the Tandilia area, retrieving various ceramic fragments that were impossible to reconstruct.

Due to an incident during his return journey, he made hypothetical reconstructive sketches of his findings, and classified each one of the areas in official cartography. At the beginning of the 50s, his many writings and theories were untidily cluttering his studio.

Living on a modest pension and in his cousin’s house, he dedicated to completing the ideas that would finally leave him alone and in the old house in Montevideo, where he died at the age of 65.

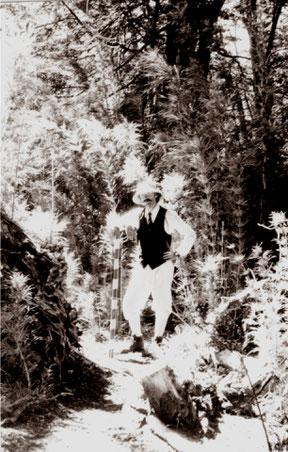

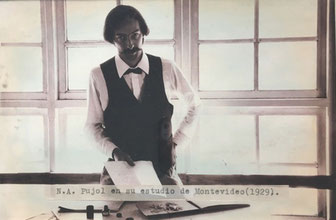

N. A. Pujol en su estudio de Montevideo (1929)

Medida: 18x13 cm

Foto toma directa intervenida

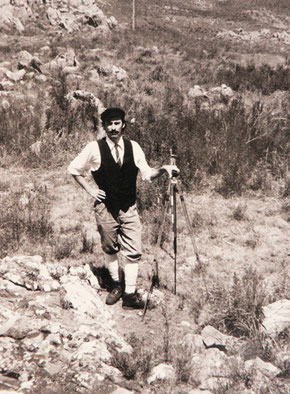

Estanislao Miliyo y Eustaquio Pagés retratados por Pujol poco antes de la depresión de los años 30

Medida: 13x18 cm

Foto toma directa intervenida

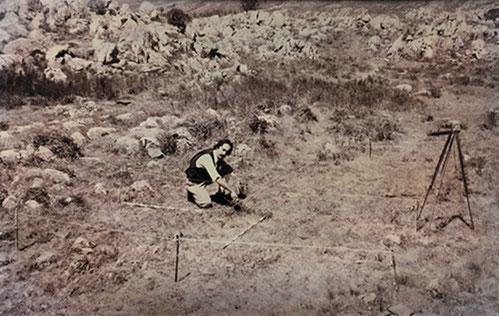

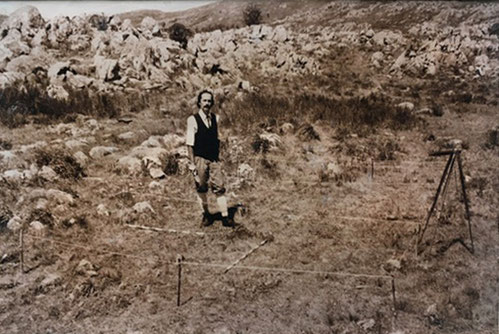

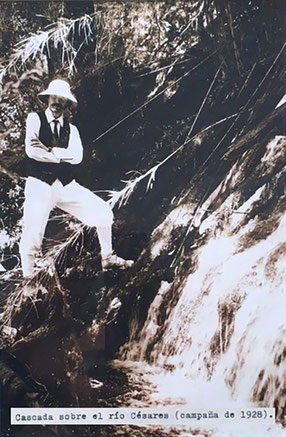

Extrapolaciones en la terraza Nº 9 Sector 3 Las Animas

Medida: 13x18 cm

Foto toma directa intervenida

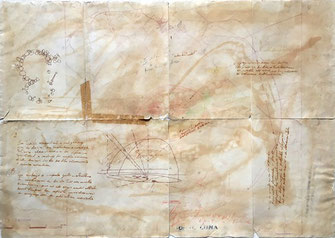

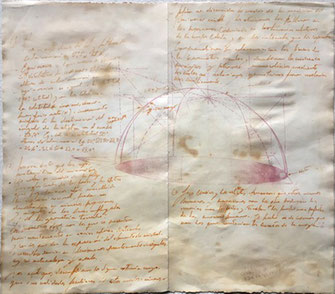

Dinergia de sitio Nº 322

Medida: 50x40 cm

Heliografía, tinta y lápiz

Traspolación estelar de sitio

Medida: 50x40 cm

Heliografía, tinta y lápiz

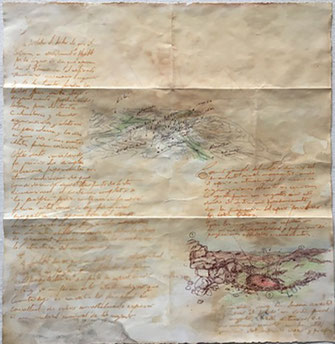

Planta de sitio La Pacífica (todos los sitios)

Medida: 35x35 cm

Heliografía, tinta y lápiz

Sitio La Pacífica

Medida: 50x40 cm

Heliografía, tinta y lápiz

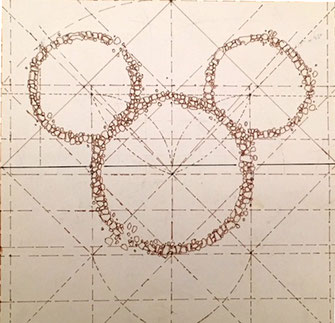

Configuración antropozoomorfa

Medida: 35x35 cm

Heliografía, tinta y lápiz

Figura antropozomorfa

Medida: 90x90x1.40 cm

Poliuretano y madera

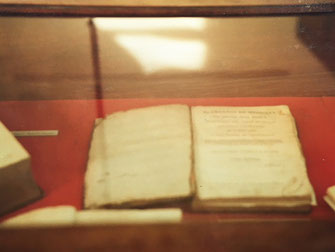

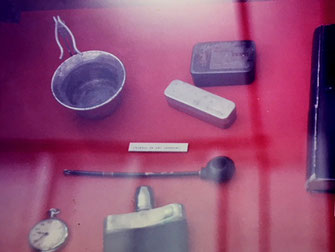

Vitrina objetos varios

Cadactrón usado por N. A. Pujol

Detalle vitrina Mapa Estelar

Detalle vitrina

Fragmentos cerámicos hallados por N. A. Pujol

Hallazgo y reconstrucción

Objetos personales de N. A. Pujol

Reconstrucción hipotética antropozoomorfa

Reconstrucción hipotética según diagramas

Vista de sala Centro Cultural Recoleta